|

Symmetry, Authority and Power |

|

|

|

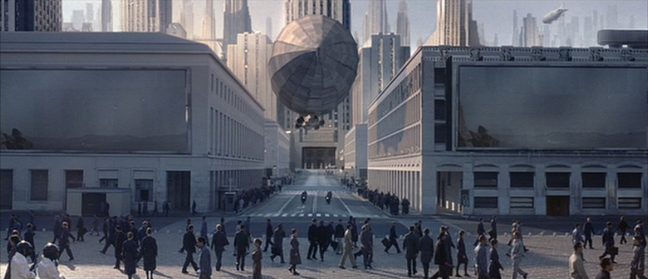

“The idealization of the city as a symmetrical motif, both in art and literature, has endured through the millennia. In Plato's Critas, the city is depicted as five concentric rings of land and water surrounding the citadel… Town planning and religious traditions of Rome were expressed symbolically in this geometric layout of the Roman labyrinth. Both the earthly and heavenly cities were reflected in this motif since the microcosm reflected the macrocosm. In Revelations, the Heavenly Jerusalem has four-fold symmetry… Utopian visions of the city from the Renaissance through to those of James Silk Buckingham in the nineteenth century involved planned cities with strict symmetrical designs. With this symmetrical geometry, order would prevail, improving not only the aesthetics of the city but also improving the way of life of the population who lived in the city…”1 Unlike the classical notion of symmetry as a spiritual or phenomenological representation of beauty, rigid symmetry in Equilibrium’s city of Libria is employed as a conscious instrument for domination. The geometrical order of the built environment removes the possibility of self-expression by establishing a very clear urban façade against which deviations are quickly noticed, and addressed. The ‘self-similar’ spaces in Libria are composed symmetrically, such that most of the system can only be observed and understood abstractly – through drawings or images of the city from above. The individual walking in Libria is subjected to spaces that cannot be differentiated from one another, and therefore cannot be understood as identifiable place. The oppressive symmetry ultimately leaves the inhabitants of Libria placeless. Additionally, Libria’s urban form emphasizes the bilateral symmetry of horizontal and vertical planes in comparison to spherical or rotational symmetry. Bilateral symmetry is a function of a single axis, rather than the multiple or possibly infinite axis available with rotational symmetry. This spatial configuration implies a unidirectional tyranny and symbolizes the oppressive conformity promoted by the Tetragrammaton. The subjugated public is relegated to the horizontal plane of the city streets and squares where they are unable “rise above” the crowd. They are easily surveyed by the vertical architecture of the Tetragrammaton. In comparison, the vertical axis, which holds connotations of power and heavenly authority, is reserved for governmental buildings and iconography. The rigorous use of bilateral symmetry and the repetition of building elements such as columns, in Libria increase the perceived depth of the scenes. They also create the feeling of an artificially produced perspective. The symmetrically composed shots focus on distant vanishing points, reflecting the single social/religious forced ‘perspective’ imposed by the government. It is also notable that the only space in Libria that incorporates rotational symmetry is the Father’s office and core of the Tetragrammaton Headquarters. These areas are circular in plan, implying that there is a variety or freedom of choices available to individuals who occupy these spaces. Additionally, there are spaces incorporated into these buildings where the axis of symmetry changes from horizontal to vertical. These spaces of transition are often a heavily guarded vestibule or forecourt to a room with a circular plan. They suggest the transition from the earthly status of the public to the godlike or heavenly status attributed to the government. Domes in classically inspired churches or that of the Pantheon, are examples of such a shift from the horizontal to vertical axis to symbolize the transition from the worldly to the divine. |

|

Bilaterally symmetrical spaces in Libria reflect the oppression of the people by the goverment. In comparison, spaces configured with rotational symmetry are reserved for people of power. ex. guardhouse and "the father" |

|

|

|

|

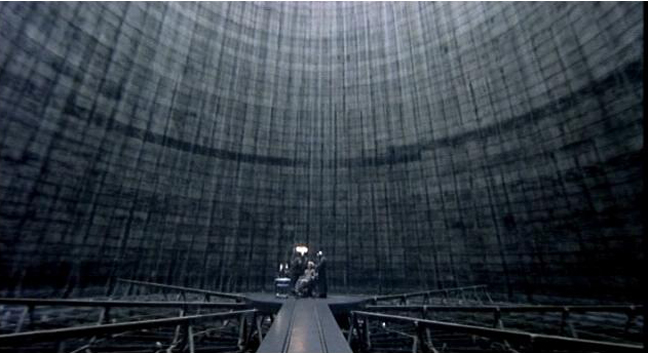

Terry Gilliam’s Brazil also contrasts vertical and horizontal axes to symbolize power relations. The architecture of Ministry buildings relies on the extreme verticality of interior spaces, specifically over scaled doorways, and massively high ceilings, to create a sense of grandeur and authority for the government. These spaces diminish the importance of the individual inside. The buildings also depend on rigid bilateral symmetry to represent the order and authority of the government. However, in contrast to Equilibrium, the asymmetrical and chaotic environment of the city outside of the Ministry belies the effectiveness of the bureaucracy. Brazil also uses rotational symmetry to represent power with the cylindrical form of the torture chamber. Again, this environment is configured along the vertical axis, highlighting the power of the Ministry. However, in contrast to the circular plans seen in Equilibrium, the floor of the torture chamber is accessible from only one horizontal axis (the gangplank structure which connects the torture chair to the entrance). This contradiction between the multiple horizontal axes of a circular plan and the single direction of the gangplank emphasizes the futility of escape. The configuration also makes Sam’s escape into madness the only possible solution. In A Clockwork Orange, the symmetry of the panopticon also sets up a dichotomy between bilateral and rotational symmetry. The bilateral symmetry of the prisoner wings creates self-similar spaces that prevent the differentiation of one side from another or one person from another. This environment oppresses Alex’s highly individual character because his is unable to react against a backdrop of similarity. In contrast, the location of the guardhouse at the centre of the panopticon, where one has the privilege of surveillance, represents the dominance of the prison guard over the inmate. This is also the only circular shaped space in the plan and therefore the only space that is configured upon the vertical axis. The contrast between the axes reflects the contrast between the occupants and the oppressive power relationship of the prison over the prisoner. 1. Morrison, Tessa. (2005) “The Symbol of the City: Utopian Symmetry” International Journal of the Humanities , Vol. 3, Issue 5 (93-104) |

|

| Next |